The Prize Paper, from The Manxman, 1912

By C. F. Denton

“I come away built up mentally and physically and with a better conception of men and things”

If you have lived in an English manufacturing town, I dare say you know the “feel of the gasp” to get away from the belching smoke stacks, the bricks and mortar, and, out, into God’s great green world, into the unconfines of some far off pasture land where in one may live that life of breadth and freedom, be got of open spaces, flowering meadow lands, and the scent of wild hawthorn and jasmine, until you shriek because of the joy of living.

But you ask, sir, is this Utopia, or is it really to be had? It is really to be had! Thanks to Mr Cunningham’s fertility in evolving and creating his great white canvas city on the slope land of glorious old Douglas Bay.

I shall endeavour to give you some idea of this charming resort, and life there, although it must of necessity be a very imperfect idea, for like all great things it is “outside” language, and you must be “it” just to feel the pull of it all. Four whit weeks ago, chancing to read a Magazine article, extolling the advantages of a camping holiday, I had an impulse, and quite by accident, my choice fell on the Cunningham Holiday Camp in the Isle of Man. I shall ever give thanks for that impulse, and for that accident. I am fairly strong and was quite prepared to reasonably rough it, therefore I looked forward with the utmost pleasure to my holidays, for as I shall tell you later the realisation in this case at all events, was the absolute consummation of my anticipation and desires. Alas! For we poor mortals, it is not always so.

I crossed to the island in one of those fine Manx steamers. The day was ideal – a sun hanging high under an arching canopy of opalescent blue, and oh! the gentle breeze over the limitless expanse of sea came into my lungs, like the breath of resurrections. On landing, I boarded one of the camp charabancs and in ten minutes stood outside the entrance of the camp. Mr Cunningham was awaiting the “new arrivals,” and his face was good to look upon, – strong, virile, and kindly. He made us welcome, with that perfect good-fellowship and bonhomie so characteristic of him, then said “take your bags into your tents and come along to tea.”

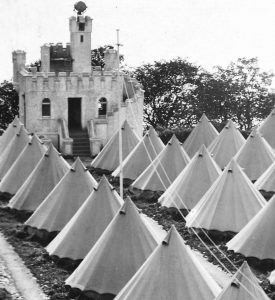

On emerging from the hall overlooking the “field,” such a vision burst upon my view as I shall never, never, forget – line after line of clean, white, military bell tents, shimmering in the white sunshine, their canvas lazily rippling before the gentle breeze – hundreds of them – and underneath, at the foot of the cliff a sea of glass and of silver and beyond was silhouetted the Cumberland hills. With a ceaseless whir of the loom in my memory, and the busy traffic of a large commercial centre still in my thoughts, the atmosphere mentally produced was balm to my tired nerves.

I went into Camp, quite “on my own,” but ‘ere five hours had passed I had made more good friends than I think in all my life previously.

In the camp there is a bond – an indefinable something, which makes for camaraderie and esprit de corps, every man gets “his feet,” from the sons of M.P.’s, Doctors, and Students, down to the humble pit lad they were all gentleman! My first night under canvas was the most blissful experience yet in my history – cool fresh Manx air circulating itself in, and out, no draft; and there I lay listening to the gentle soughing of the wind among the tents, and the soft lap, lapping of the sea on the sands beneath the brow – and so I slept! I woke at 6am an already new man. I had forgotten the factory. I was refreshed to juvenility, and so heard the call to live.

I hastily donned an overcoat and repaired me to the large plunge bath (about 90 feet long) wherein I disported myself to my heart’s content, and it was good!

Breakfast was served at 8am and such a breakfast, – fit for a King – fresh oaten porridge, plenty of new Manx milk, ham and eggs, an unlimited supply.

Then commenced the day. One of the fellows called out, – now then, “Manchester,” will you join a party to Port Erin? Of course I would. We lined up outside (250 strong), purchased our tickets at the camp office “en passant, may I say all fares to campers are about half ordinary”, one of the boys brought round Japanese parasols and just a few tin bugles, and so with these emblems of merriment and holiday making we marched in orderly procession to the train.

That first night and day will live as long as I have memory. We revelled in the sunshine, we bathed in the briny, and dried ourselves beneath the old rays of Old King Soul just as our remote ancestors did. Oh, the pleasure of that first day!

It was the first of many delightful days, and now after four seasons of living in Mr Cunningham’s camp, I can unhesitatingly say that it is better every time, except for that new fresh day when everything to me was so surprisingly new.

My subsequent days were spent either laying in camp, or having a sunbathe outside my tent, or walking to the many silver nooks which are bound in dear old Manx land. And so the days flew by amidst perfect environment, in the company of the very best of fellows, and with no roughing it as I had thought, but rather a life bordering on the luxurious and all of it lived in God’s good fresh air.

The camp “sing song” is one of the important weekly events; there is a good little camp orchestra, and a host of camp talent and a room (accommodating 2,000 people) full of holiday makers, the fun is fast and furious, and all of it the best possible fun, clean, healthy, and pure.

I have been in camp too when the wind howled, and the rain poured down, as though the cisterns of the sky had broken up, – I felt nothing of it in my snug little tent.

On these wet days the indefacitable Musical Director works up impromptu smoking concerts or games are indulged in, or boxing bouts are arranged so that there is never a dull moment however unpropitious and inclement the weather may be, and these all under cover of the spacious Recreation Room.

It is quite impossible to adequately furnish any real idea of the life here, for it is so kaleidoscopic, so changing, so varying as to create many new phases in one day but the garment covering all is a composite of jollity, happiness, health, and entire good feeling!

The good things synonymous with Mr Cunningham’s camp are abundantly testified to each year by the ever increasing applications for residence there, indeed, I have personally known fellows to say, “ah! well if we cannot be taken in camp, we shall not go to the island this year,” not, mark you, because of the extra expense of living in a boarding house, for that they could well afford, but because once under canvas amid such perfect conditions, house-living is out of consideration.

I have gone to camp when the whole world held a smile for me, and I have gone, too, when my heart was very heavy, and life seemed to hold but little of good, but whatever my mood or my mental condition, I have always come away built up mentally and physically and with a broader and better conception of men and things, and with a longing for my next holidays and my return, to the dear old Cunningham’s camp, which means so much of joy and everything good to thousands of Lancashire and Yorkshire boys.

Charles F. Denton.

Note by the editor. It will be remembered that, last month I confessed to not knowing as much about the camp as I ought to. Accordingly I ask campers themselves to instruct me by means of a little competition. it was a success and the full going has won. If Mr Denton will apply to Mr Cunningham he will receive a ticket for Douglas to Dublin and back. Why not keep the idea up, all season? Yes, let campers, go ahead. Incidents of camp life written on postcards will do. Campers’ camp “snapshots” are equally eligible. Will Mr Arthur Clark (Sheffield) kindly send us his address? – ed. “Manx man.”

Photo: Look-out tower, which doubled as a latrine. Collection of Mike Kelly